Writing About Contemporary Art with YI TING LEE

I was introduced to the lovely Yi Ting through a close friend. Yi Ting is an editorial assistant at Burlington Contemporary. She sat for a coffee with me and we talk about her background, her work at Burlington Contemporary, and her thoughts on the contemporary art scene in London.

Chatting with Yi Ting in London

Tell me about your background.

I grew up in Hong Kong and I initially studied economics in university and then half way through I realised it wasn’t for me and fell in love with art history, which became my path. I wanted to pursue a masters in art history after my undergraduate degree, but I delayed it for a year because covid happened. In that year I was a research and teaching assistant, and also worked as an editorial assistant for an art publication with a focus on Asian art. In 2021 I moved from Hong Kong to London to do my masters at the Courtauld Institute of Art, specialising in Qing period Chinese art history.

Not contemporary?

No, not contemporary at all. I worked part-time at a small ceramics gallery in Hampstead after I completed my master’s degree. When I saw an opening for a part-time opportunity to work as an editorial assistant at Burlington Contemporary, I applied and was very fortunate to have got the position. After a while I stopped working at the gallery, and started working at the Burlington as their partnership executive. So now I’m working 3 days as an editorial assistant and 2 days as partnerships executive.

Some background information on The Burlington Magazine maybe?

Yes.

It’s a well-established print magazine devoted to art and art history that has been published monthly since 1903 – even through the two world wars.

In about 2018 they launched Burlington Contemporary, which is an online platform dedicated to contemporary art that publishes weekly. It focuses on contemporary art in a way that, I suppose, the printed magazine can’t quite do in the same way since it doesn’t move as quickly. There’s also a long historical legacy to The Burlington Magazine that frames its content and readership; as a digital site with the same commitment to research and academic rigour, Burlington Contemporary offered a new avenue to reach an audience with serious interest and dedication in contemporary art.

There are a few publishing strands on Burlington Contemporary: the weekly publication, which are usually exhibition or book reviews, artist interviews or conversations, and artist profiles; and the peer-reviewed academic journal published twice a year. We also have an annual Burlington Contemporary Art Writing Prize, where the winner is award £1,000 and have their winning review published on the site.

I’m more involved with these publication processes as editorial assistant. For the other 2 days of the week, I work in the partnerships department. At the moment we’re trying to make Burlington Contemporary more sustainable as an open-access platform, since we’re a charitable organisation.

Oh I didn’t know that.

Yes, the goal of the organisation is to promote critical research and writing in art history. We occupy a very special position, in that most contemporary art publications who publish as frequently as we do are not charities. This position gives us a lot of editorial freedom, which is generously supported by patrons and organisations who believe in what we do. Content on Burlington Contemporary is really dictated by what the editorial team deems interesting, meaningful and important, not only to an immediate audience, but also in terms of art historical value and being a resource for future research.

How big is Burlington Contemporary?

We have about 14–15 people in the whole office, including 7 in the editorial team.

So why didn’t you study contemporary art?

It wasn’t intuitive for me because it felt a bit impenetrable and intimidating because I didn’t grow up going to museums or seeing a lot of art.

Why did you choose art then?

I was always interested in art and literature, although I tried to veer off this path because I thought I needed a ‘real job’. I took the odd art history class in university out of interest, became really invested and ended up majoring in art history.

I feel like people see that I’m Asian and think it’s natural for me to study Asian art, but I actually started with Western art and moved towards Asian art because I was really inspired by my professors in the Asian art department. There is an element of relating to the cultural sensibilities as an Asian person, but it really is more of a discovery process for me.

Perhaps because of Hong Kong’s colonial history, all the artists I knew growing up with were Western artists. If I hadn’t studied Chinese art, I probably wouldn’t be able to tell you many names of Chinese artists throughout history. When I started taking Asian art courses, there was a strong sense of ‘oh wow, I didn’t ever think about looking at the world from this perspective’.

As students we were told to look deeply ‘into’ Chinese paintings. Reading a scroll is completely different to the way you would engage with a canvas hanging on a wall. Stone Cliff at the Pond of Heaven (1341) by Huang Gongwang, one of the Four Masters of the Yuan Dynasty, is a really good example of this. You’re meant to ‘enter’ an ink painting: in landscapes on vertical scrolls, you start from the bottom, follow a trail up through the mountains and into the sky, where there’s often a poem or calligraphic text. When interpreting Chinese art historical works, you read into the artist’s cultivation as a literati scholar and its relationship with their artistic practice. It’s supposed to be a meditative process – a kind of elevation.

I remember the distinct moment when I realised I had never looked at a painting that way. It opened up to me a new way of looking at art, and also the world.

Fascinating. I never knew this about Chinese art.

Growing up I think people were always saying to take a step back to look at a work on the wall. But in Chinese art you step forward, look closely, look deeply.

So then which art do you prefer now?

Both. I was drawn to Chinese art of the Ming period because there was a lot of questioning about the self, identity, representation and authenticity, and visuality. I also found it really fascinating when I learn about Indian Modernism to think about the search for a shared visual language, nationalism, and the reflection of existing knowledge structures.

These thematic interests – the exploration of self-identity and how one situates themselves – translate to arts of different periods and are present in many works of contemporary art. Thematically there’s a common ground for my interest in both contemporary and more historical works of art.

Installation view of Jes Fan- Sites of Wounding- Interchapter at Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York, 2024, showing, in the centre, To Shed, by Jes Fan. 2024. Soy Skin, metal and epoxy, 157.5 by 94 by 45.7cm. (Courtesy the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; photograph C. Creagan).

Who are some artists that you are looking at right now at Burlington Contemporary that excite, surprise or interest you? Why?

We published an artist profile on Jes Fan, by Sophie Guo. I've not seen Jes Fan's work in person, but I find it really fascinating to read about their investigative approach to finding meaningful parallels and disjuncture between our social structures – which are influenced by our histories and cultures – and the ecological systems of materials they choose to use in their work. There's also a sense of affinity because they explore diasporic identity and the colonial history of Hong Kong, which is where I'm from!

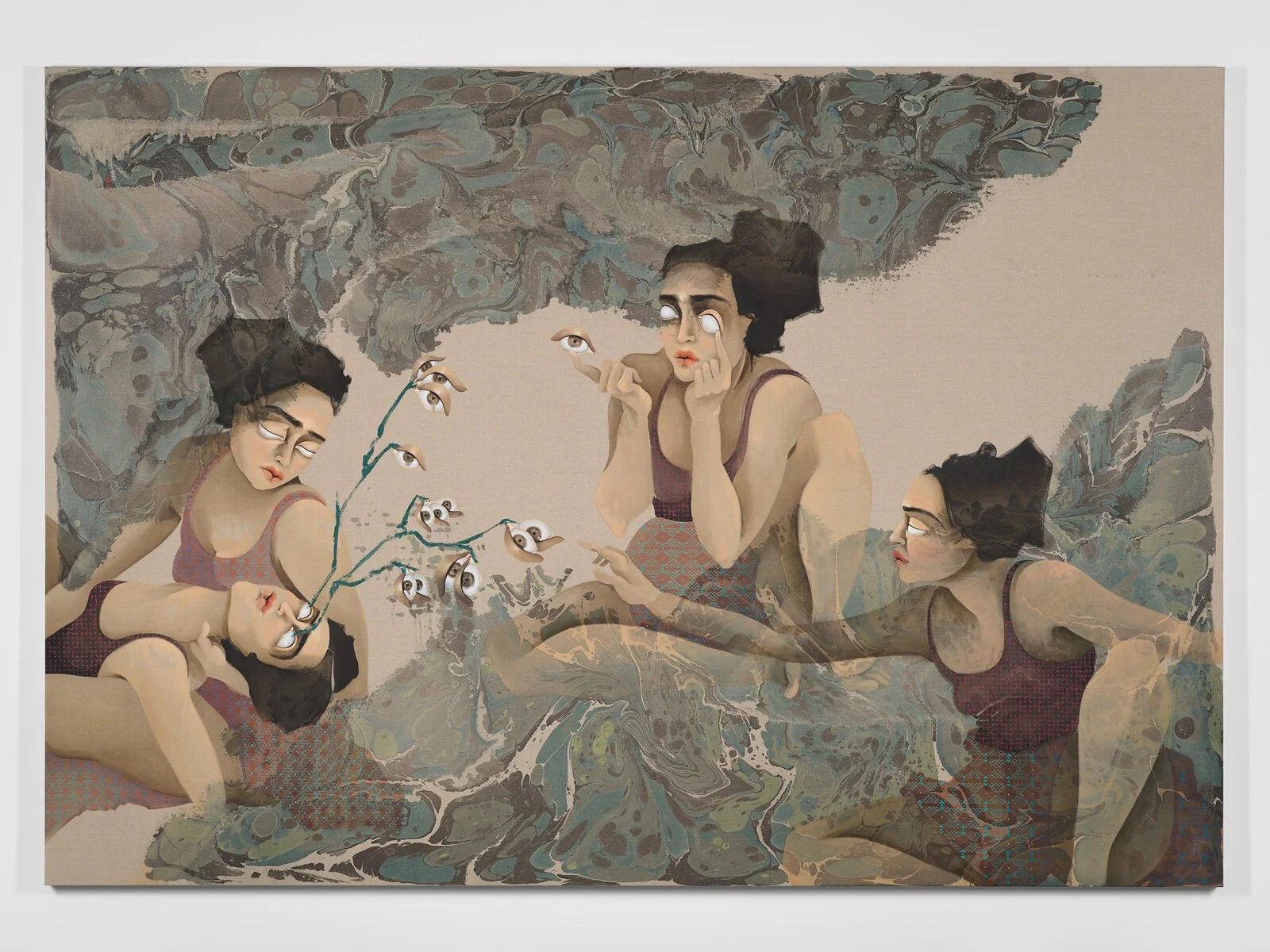

Hayv Kahraman also explores some of the same themes – thinking about the body, knowledge structures and boundaries, but in a very different way. I love her paintings because they are so beautiful and elegant, but at the same time provocative and personal.

Hayv Kahraman, Eyeris, 80 x 115 inches, Oil and acrylic on linen, 2023

We also, somewhat recently, published two artist dialogues: Dexter Dalwood and Rosalind Nashashibi, and Patricia Domínguez and Suzanne Treister. This content format foregrounds the artists' perspectives, and I have found it really rewarding to read about their practices from their conversations with like-minded peers.

Tell me more about your role as a freelance writer.

This is relatively new to me, I usually pitch to the editors of a relevant publication when I come across an artist or exhibition I want to write about. It’s really important to consider the background and tone of the publication. For example, if I wanted to write about a research-based artist I might pitch to Burlington Contemporary. Whereas if I came across an artist and wanted to focus on their specific Asian heritage, then I might pitch to Art Asia Pacific. A lot of freelancers and critics write for multiple publications.

Taken from Yi Ting Lee’s article: Installation view of Trevor Yeung: Soft ground at Gasworks, London, 2023, showing Soapy Fuck Tree, by Trevor Yeung. 2023. Soap, oak bark powder, moss, selection of essential oils, glitter, fiberglass and metal, dimensions variable. (Photograph Andy Keate).

Tell me about some work you’ve done that you’re really happy with.

The first piece I wrote for Burlington Contemporary will always have a special place in my heart. It’s an artist profile of Hong Kong artist Trevor Yeung, before represented Hong Kong at the Venice Biennale. I anchored the profile with Trevor’s show at Gasworks, where the predominant work is a wax ‘fuck tree’ sculpture. He created a replica of this tree in Hampstead Heath, infamous as a ‘cruising’ site.

“Cruise”?

Yes, it refers to the act of seeking out sexual encounters in public areas. He explored the emotional and sensual aspect of cruising, and the human entanglements with this tree. The ‘fuck tree’ has been used for this purpose so much that the trunk has actually bent, almost like a bed. He’s interested in our relationship with nature, and the parallels between ecological and social systems that govern human behaviour. He tried to encapsulate the atmosphere of the place in this large, life-sized wax cast of the tree, integrating elements of touch and smell into this installation.

Tell me about an artwork that’s inspired you.

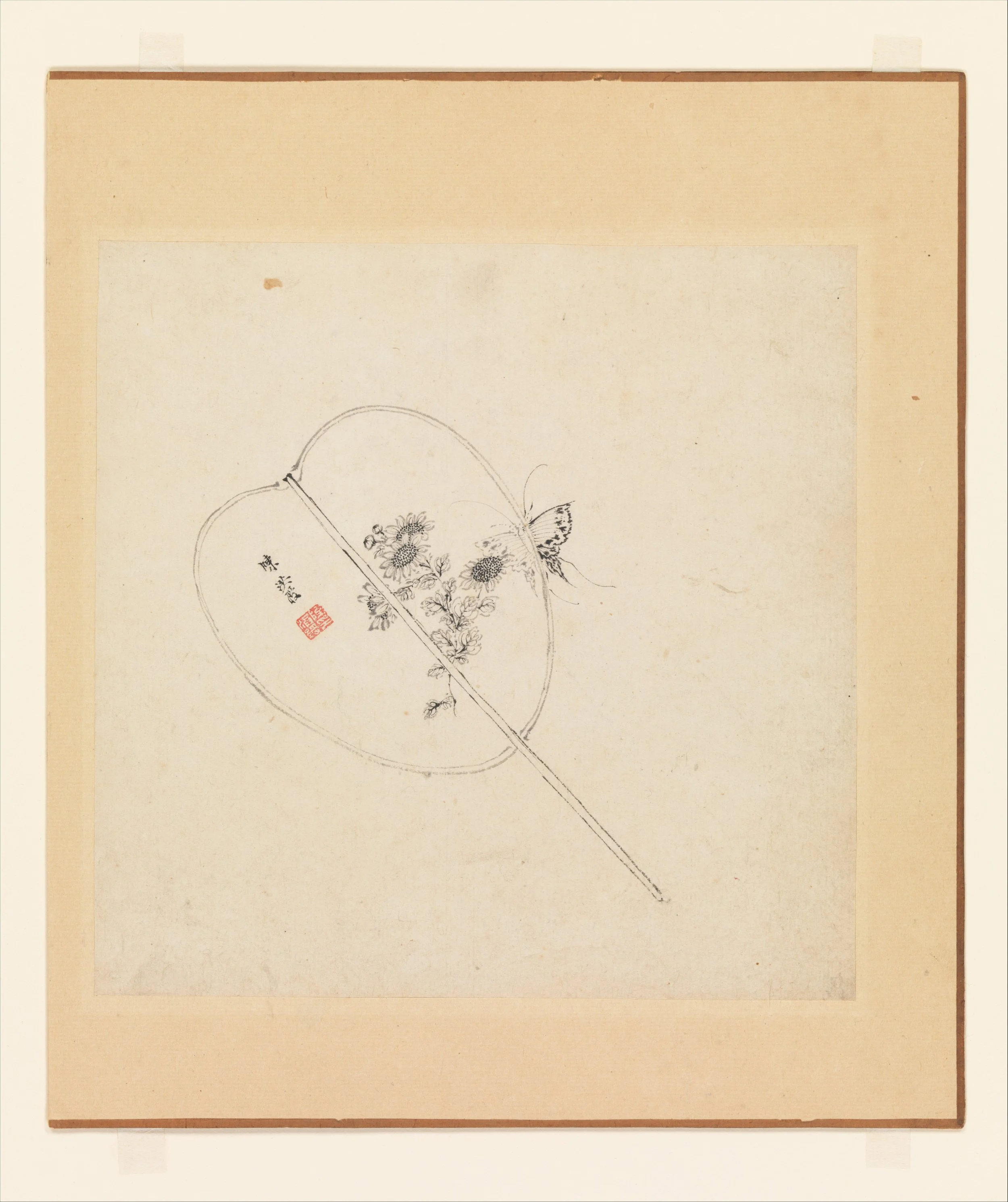

The seventeenth century “Miscellaneous Studies” by Chen Hongshou – I just love his work. It’s an album at the MET in New York with 12 leaves. You’re meant to hold and leaf through it, which is a tactile way of engaging with art. In one of the leaves, he painted a butterfly half in and half out of a fan, which has painted chrysanthemums on its surface. It’s a nod to the illusion of painting: is the butterfly a picture or is it ‘real’ in the sense that it can be attracted to the painted chrysanthemum? Ultimately it is a painting of a painting; he even signed his signature within the fan. It’s all very meta.

Kind of tromp l’oeil but in a totally different way.

Yea, it’s almost like a mental tromp l’oeil.

Chen Hongshou (1598-1652), Miscellaneous Studies. Fan and butterfly. Album of twelve paintings, 1619. Metropolitan Museum of Art

It also alludes Zhuangzi’s butterfly dream. In it, he dreams he is a butterfly and wakes up wondering whether he was a man who dreamt of being a butterfly or whether he was a butterfly who dreamt that he’s a man.

A bit Kafka-y

A lot of Chen Hongshou’s work questions the theatricality of performing within the parameters of social structures and customs. It’s very modern concerns set in the seventeenth century.

What are your thoughts on the London contemporary art scene?

I really value the ecosystem of the London contemporary art scene. There’s a healthy mix of commercial and institutional representation, investment, public interest, community-led projects, artist-run spaces and initiative, grassroot movements, non-profit organisations… There’s also an active audience for contemporary art and writing, and there are quite a few publications. It comes together to form a foundation for contemporary art to grow and for actors to live within that space, and to enter it as well. There are artists practicing at all different tiers.

I have an extra level of appreciation because the Hong Kong art world grew in a very different way. Art didn’t permeate the society in the same way and my parents didn’t take me to see art growing up – it’s less commonplace. There’s a few new museums over the past few years but it’s really a recent development.

Challenges for the contemporary art scene?

A lack of support for artists and art organisations from the public sector. As much as I appreciate this ecosystem, it’s driven by a lot of care and passion rather than compensated efforts. In the face of other challenges and seemingly more pressing issues, it can be hard to quantify and explicate the benefits of art, even though the arts and creative industries give this country, with its rich cultural heritage, an edge. I think it’s an industry that’s worthy of more investment.

Also, art can bring people together, which is so valuable now because so many other forces can be divisive. An exhibition or a work of art can heal and inspire people, and make communities feel acknowledged. Culture is an important fabric of society; how people feel matters, even on a practical or economic, political and social level, because it impacts how each individual will contribute to the wider society.

Favourite London galleries?

Tate Modern is an obvious go-to. I also enjoy shows at the Barbican and the Hayward. At the Camden Art Centre and Whitechapel Gallery, you can tell the curators really put thought into their exhibitions.