Cultivating Arts and Culture with MARGUERITE NUGENT

Meet Marguerite Nugent, the driving force as Cultural Director at Culture Coventry Trust. Beyond overseeing the city's cherished arts and heritage venues, she's deeply invested in cultivating the next wave of creative professionals, ensuring opportunities for young people from all walks of life. Her passion lies at the intersection of preserving culture and building a vibrant future for the arts.

What drew you to art to begin with.

I grew up near Birmingham and used to go to Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, quite often. My Dad would take us there when he was giving Mum a break at the weekends. It was quite special time because he was so often at work so it was a novelty to do things together. At BMAG I was really inspired by the pre-Raphaelites. As a child I just loved the colours and the stories behind them. They were so opulent and lush. That’s what ignited my interest in museums, but I was always interested in history at school too. After I left school I went to work in Paris as an Au Pair and I think I must have visited every museum in the city! That’s when I started to wonder about how I could go about working in a museum or gallery.

Marguerite in Venice for the Venice Bienale judging panel

Tell me about your career journey.

I started out working at a small gallery in Colchester called Firstsite, originally named The Minories. Then I got an Arts Council traineeship at Wolverhampton Art Gallery, working as a trainee exhibitions curator, which I really loved. I’ve always loved the dynamism of temporary exhibitions. I’ve worked with collections as well, but what I really enjoyed was creating and presenting a show for an audience. I think it was the story-telling element appealed. I was in Wolverhampton over 25 years in various different roles. By the time I left I was the Arts and Culture Manager for the City Council, managing three sites plus the city archives. I was also the strategic lead for culture within the council. During my time there we hosted the prestigious British Art Show 9, so I was involved in establishing a partnerships and using the exhibition as an opportunity to strengthen the arts ecology in the city .

Whilst there I completed an MBA with a focus on cultural leadership. I’m really interested in how culture can become more sustainable, developing good business models and commercial principles that can be applied to the sector. An opportunity came up in Coventry to take on a short-term organisational change role. The company, CV Life, had recently bought together cultural and arts provision and wanted the align the two arms of the business more closely. those two more closely together. I took this on initially as secondment for one year and now I’m in my third year with the company.

What sort of things are you trying to achieve in this role?

First and foremost, strengthening and sustaining the business during a challenging time for the cultural sector. Linked to this is increasing engagement. I’m particularly interested in breaking down barriers and increasing access to culture. That’s been at the heart of my work for many years and has been embedded in many of the places where I’ve worked. Wolverhampton Art Gallery had this ethos about access to art dating as far back as the 1970s. Curators there really wanted to appeal to a wide audience and hosted a very wide variety of exhibitions from contemporary Pop Art to Seaside souvenirs. They weren’t just catering for those who are comfortable within the arts environment or well-informed about the art, but for all local people. Now this seems a given in museums and we talk about ‘place-based’ working, but Wolverhampton was really leading the way back then.

Collecting Coventry

The other area I’m interested in is opening up access to creative careers. If we have greater diversity within the workforce then we have more diversity of thinking, better ways of doing things, leading to more exciting and innovative practice. There is a real correlation between diversity and business success. However, it’s a big challenge for the culture sector to change because there are many social, psychological and financial barriers to entering a career in the arts. I made this a focus in my roles as chair of the Cultural Education Partnership in Wolverhampton and I’m also part of the Executive Group for the Coventry Cultural Education Partnership. It’s about finding opportunities for young people to gain and insight into creative careers and build cultural capital. Sadly so many young people face barriers that we are not able to solve as a cultural sector alone.

Do you look a lot at the strategic side of how art impacts the well-being of people?

Yes, definitely. It’s an interesting challenge: thinking about how we can be financially sustainable, but also how we can support health and well-being. We essentially need to be accessible and support the most vulnerable, but at the same time we need to be a successful business. CV Life’s mission is very much about improving health and well-being and tailoring programmes to the needs of communities. I work closely with our Social Impact Director to raise awareness about the impact of the work that we do within our museums. We regularly develop community engagement projects that relate to our exhibitions. For example, we have a community garden at The Herbert, where people from refugee and migrant groups volunteer. This was developed on the back of us hosting Dippy the diplodocus on loan from the Natural History Museum for three years. Last year we hosted “Collecting Coventry”, and exhibition that showcased many of our collections and was intended to give visitors the feel of being behind the scenes in our stores. We held a number of focus groups to find out what people would like to see both as part of exhibitions and also within our collections. We asked them about how represented they feel. We’re using the findings to develop new plans for exhibitions and displays and also as a model for future consultation.

How instrumental is data in revealing the value of art and its benefits to society?

It is and it isn’t. Quantitative data that tells you about reach and types of audience is useful to measure success but really you also need to capture longitudinal data to understand the deeper impact of different programmes. You might run a program and those participants may not feel the benefits for many years later. We collect a lot of data, including qualitative data about participant experience etc. but I’m not sure we always use this to its full advantage. I’d say it’s a bit of a work in progress.

In what ways are you engaging with art in your role?

I love working with artists. It’s that happy marriage of working with artists to get their work seen and help them to develop their practice, whilst also bringing more people in to appreciate and enjoy seeing it. Working and discussing with artists, how best to interpret and display their work to convey meaning is exciting and challenging. These days I’m not doing so much hands on curating but I try and keep up to date with the art world by attending exhibitions and events like Frieze Art Fair and Venice Biennale whenever I can. Actually I spent quite a lot of my spare time in galleries!

I would say that as an institution we engage with artists on both a local and national level. We’re quite well integrated on a local level with art societies and networks in Coventry. We programme a few different shows where local artists get an opportunity to exhibit: one of which is the bi-annual Coventry Open exhibition; another is the Coventry Artists Societies Exhibition. In addition we’re about to launch hire spaces where artists can hire space at a very reasonable rate to show their work. With the national side of things, we work a lot in partnership with other organisations like Tate, through their Artist Rooms scheme, or Hayward touring, by hosting their touring shows. Then we also have Dippy the Diplodocus on loan from the Natural History Museum. We make acquisitions of artists work with support from Art Fund and The Contemporary Art Society amongst others.

Getting out and seeing exhibitions is really important just to keep an awareness and knowledge of what’s going on out there and who the emerging artists are. You never know when this could lead to an exhibition or to us acquiring new work for our collection.

Chila Burman’s Tuk Tuk

Any artists you’re really into at the moment?

I find Chailya Burman’s work really interesting. I’ve worked with her going back many years. She was one of the women artists associated with the Black Art Movement of the 1980s and has recently undertaken many public art commissions as well as having a solo exhibition at Compton Verney this year.

Yes, I’m familiar with her work for the Art of London.

A few years ago, when I was working there, we held a show of her work at Wolverhampton Art Gallery, which was all based on her father’s ice cream business. Her work has a pop-art aesthetic, which meant that it fitted in really well in the context of the permanent collections. What I like about her work is that it’s very accessible and also humorous, whilst also conveying an important message about culture and identity. It’s visually striking, but it also has this really interesting story about her and her family’s experiences coming into the UK and her life growing up. You can experience it on a number of different levels.

Fiona Banner is another artist who is really interesting. She showed some work at an exhibition called ‘Divided Selves’ that we hosted at The Herbert Art Gallery and Museum last year. She works with a lot of text and also focuses on themes of conflict. Her film ‘Pranayama Organ’ was shown in ‘Divided Selves’. It was filmed during Lockdown and features two inflatable military aircrafts in the form of costumes worn by the artist and a friend. They are engaged in a kind of ambiguous battle, accompanied by a haunting soundtrack. It was very popular with audiences, including families. The seating took the form of beanbags that echoed the parts of the jets in the film and were particularly popular with the children. On a typical day you would encounter families stretched out on the bean bags immersed in the film and groups of buggies lined up against the wall.

Fiona Banner, DISARM, 2024, 4.41 min. Screened on Piccadilly Lights as part of CIRCA 20:24 Programme, London, UK

So you work more with contemporary art?

Yes, I suppose I do. That’s probably partly because of the places I’ve worked. We’ve tended to collect contemporary art because it’s more affordable than historical work and also because we want to represent society and collect what feel relevant today. Working with regional collections you need to have many skills but I would say my main area of knowledge is post 1960s British and American art with a focus on conflict and issues about society and economics. In Wolverhampton there is a big collection of work about the Troubles in Northern Ireland, which is quite unique. The Pop Art collection there touched on many political themes including modern conflicts in places like Vietnam and Bolivia. We also collected work related to the conflict in Israel and Palestine, partly looking at the way that conflict parallels what happened in Northern Ireland. Then at The Herbert you’ve got the peace and reconciliation collection because Coventry is known as the City of Peace and Reconciliation having been famously blitzed during the Second World War and having to rebuilt itself in the 1950s. Both cities have played an important role in the history of the British Black Art Movement too but until recently those artists weren’t really represented in the collections. This is also an area that we’ve been trying to address within our collecting policies. It’s important to be able to stand back and assess gaps in collecting and then fill in those gaps as part of future priorities.

Describe the arts scene of Wolverhampton.

Wolverhampton has a growing art scene, it’s a smaller town than Coventry. British Art Show toured there in 2022 and this had a big impact in terms of putting it on the map culturally. Local stakeholders really saw the value that culture could bring and Wolverhampton City Council even submitted and EOI to host City of Culture 2025 (taking place now in Bradford). I don’t think that would have happened if it hadn’t been for the interest in British Art Show. Both Wolverhampton and Coventry have really great art schools as well.

And Coventry?

In Coventry we were awarded City of Culture 2021, where the benefits were felt more at a grass-roots community level. There’s a really vibrant art scene in Coventry and the region with about 12 art societies and several artist’s studio spaces. It’s nothing on the scale of London though, which is a challenge. The opportunities regionally are not really the same as London, where the art market is principally focused. There are some challenges for artists being based locally, including lack of studio spaces and opportunities to exhibit. This is one of the things that we are we’re trying to support.

What are some other frustrations you’ve come across?

One of the obvious things is funding. That’s an issue everywhere. The reduction in public funding is having an impact across the country. There’s also the need to look at other business models, which can be exciting but also challenging because of the speed at which you need to make something work and generate income. There are challenges around the increase in costs: national insurance and the rising minimum wage have an impact so there is the dual challenge of reduced public funding and increasing costs - basically a perfect storm. It is a really challenging time right now in the cultural sector.

There is also the challenge of engaging people and staying relevant too. You’re competing for people’s time and attention at a time when people are making careful decisions about how they spend their money and what they do with their free time. It’s a very different picture now with, compared to when my career began in the 1990s. Nowadays so much more is available digitally and you don’t have to go far to get your culture fix.

Marguerite visiting Chiharu Shiota’s key and yarn labyrinth, Venice Art Biennale

Tell me your thoughts on the value of your work on people’s mental health.

Culture greatly benefits people’s health and well-being. Just being able to see that improvement, when people engage with particular programmes is powerful. Then there is an economic benefit to society because museums can support people who would otherwise need to access services like NHS for example. We ran a ‘social prescribing’ programme that was aimed at supporting health and well-being as part of primary care for patients.

We’ve all been somewhere where we feel out of our comfort zone and for some people museums can feel like that. We want to be inclusive, not just there for the small group of people that have grown up going to museums. We talk a lot about cultural capital. This is the idea that some people grew up going to museums as a child (like me!) or they went to a school where art was high on the curriculum and this means that they have certain advantages in life. If we can provide opportunities for people to engage with culture from Early Years education onwards we can build cultural capital that benefits life opportunities and opens up different experiences.

And art is known for being quite closed off and exclusive as we all know.

Yea, definitely the cultural sector can be a lot like that. There’s a sort of language and a way of behaving that can be quite alien to many people. We need to work harder to break down that barrier.

How do you feel about that “cultural capital” being integrated at an early age?

I think it’s really important. To put these things right in society, you’ve got to start from birth. I see it in my children too. I used to drag them around Venice Biennale from an early age.

Drag is not the word I’d use if I got to go!

Haha. There was a lot of bribing with ice-cream. But now I see they go to galleries and museums quite a lot when they have free time. I do think it’s really important to embed these experiences really early. Sadly in schools cultural subjects are a low priority on the curriculum and then access to cultural education gets limited by a person’s ability to afford extra-curricular activities.

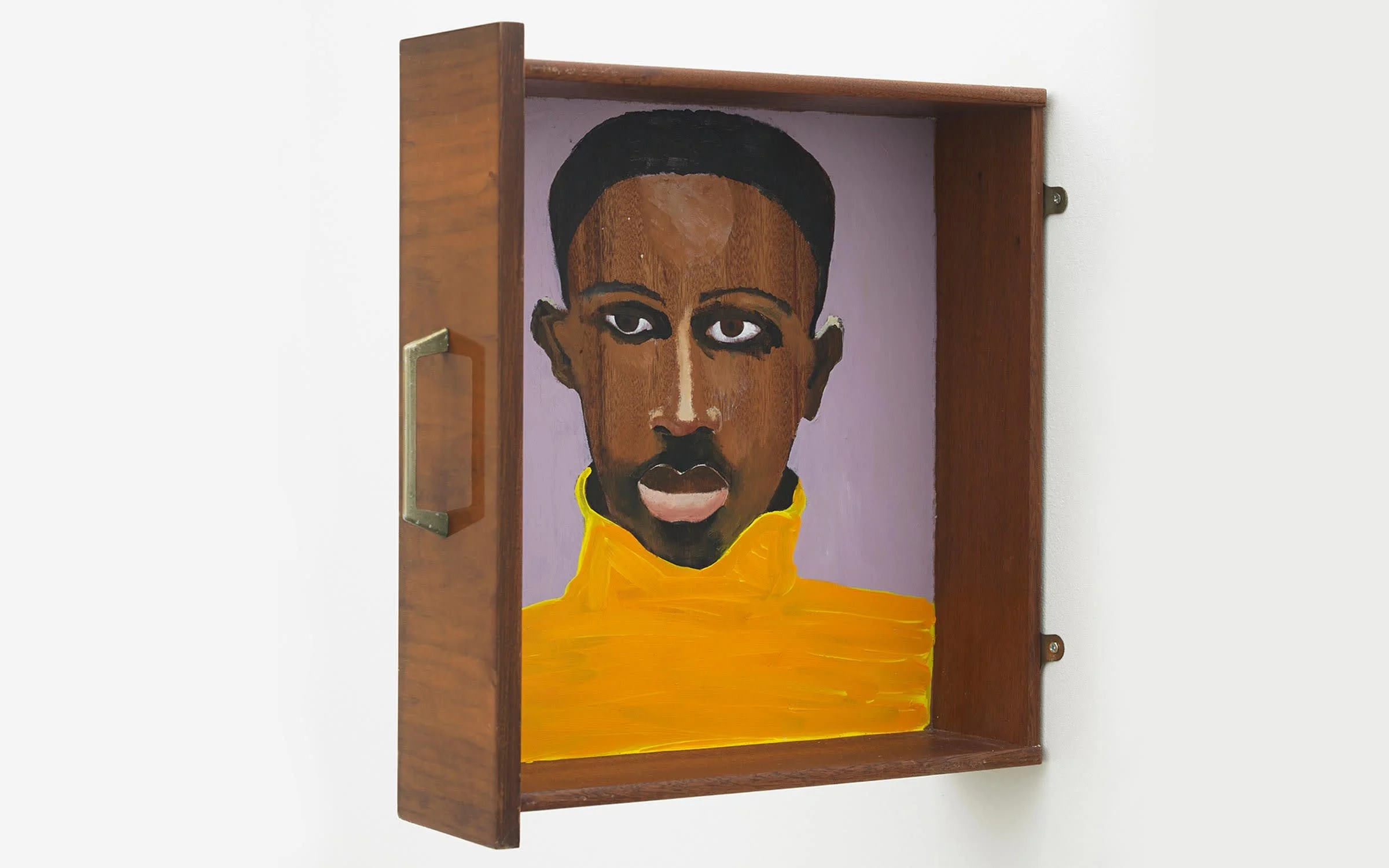

Lubaina Himid, Man in a Jumper Drawer, 2018. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens.

What can you tell me about the Venice Biennale?

Obviously it was really exciting to be invited to be part of the selection panel for the 2026 Biennale. It was very interesting discussing the ideas with the rest of the panel, who were arts professionals from all around the country. The process is very confidential as it’s important to ensure no one can influence your decisions. Obviously the artist has been announced now, Lubaina Humid. I think it was a really good outcome. I think she will do something really beautiful with the British Pavilion and I can’t wait to see the exhibition next spring. Her work is really bold, really striking. I think there’s also something about the scale she works at that will fit really well with the architecture. Also the stories behind her work are really interesting because in a lot of her work she tries to uncover stories about history that are not quite as well known.

Have you been on lots of judging panels before?

I’ve done more on a local level, so this was my first experience doing that sort of selection process. It’s going to be really interesting to see what she’s going to produce next year. I don’t know if she was necessarily an unexpected choice. Her work is really bold, really striking. I think there’s also something about the scale she works at particularly in a museum setting. Also the stories behind her work are really interesting because in a lot of her work she tries to uncover stories about history that are not quite as well known.

Subscribe to the Studio BAE newsletter now.